Christo and Jeanne-Claude: two people but one artist

They met in Paris in 1958, when Jeanne-Claude commissioned Christo a portrait of her mother: thus began a sentimental relationship and an artistic collaboration that would last for their entire life.

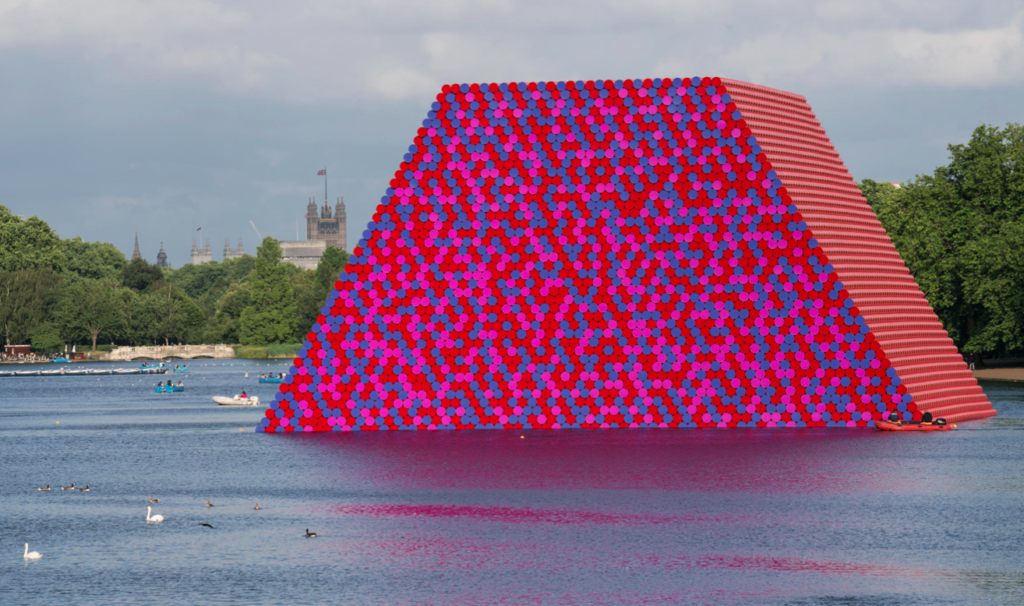

Christo e Jeanne-Claude, The London Mastaba (Serpentine Lake, Hyde Park), 2016–18

Courtesy Estate of Christo V. Javacheff

Since 1961, the year of their first intervention with an environmental work, Stacked Oil Barrels and Dockside Packages, at the port of Cologne (starting the use of textile that in this case cover “something”, and choosing as subjects also barrels that will later return in The London Mastaba, 2016-2018), they have always worked together although for a long time their works have been “signed” solely by the name of Christo – due to the difficulty of affirming the reputation of an artist, especially if a woman.

Only in 1994 they decided to officially change their name to “Christo and Jeanne-Claude”, giving precedence to his name only because he was already an artist when they met.

Even after Jeanne-Claude passed away in 2009, Christo continued with the realization of their projects, keeping both names.

Christo, Wrapped Reichstag (Berlin), 1971–95

Courtesy Estate of Christo V. Javacheff

We have always tried to categorize them by choosing a label that would represent them: but it is wrong to consider them purely land artists because their interventions are carried out in urban environments already marked by human intervention, rather than in uncontaminated spaces.

It would also be limiting to define them with the neologism wrapping artists, because if it is true that these interventions are particularly known (in particular on public buildings: Wrapped Reichstag, 1971-1995; Wrapped Kunsthalle, 1967-1968), they are not distinctive of their production: wanting to find a common denominator this could instead be the use of fabrics and cloth, fragile materials that summarize the temporary character of their works (as evidenced by Running Fence, 1972-1976 or The Floating Piers, 2014-2016).

In fact, their artworks do not last over time, resulting in an urgency of seeing them: this aspect is intrinsic to their desire to intervene but not to damage or modify, the contexts that host their works then return to their initial state, the materials used are completely removed and recycled.

Despite the often monumental size, the scale of construction is still chosen to create something that people can enjoy, experience by walking near it or crossing it: it is not a vision from above or from afar that leads to the enjoyment of the beauty for which they are made.

Christo, Running Fence

(Sonoma and Marin Counties, California), 1972–76

Courtesy Estate of Christo V. Javacheff

The two have always acted according to a logic far from the mechanisms that animate the classical art market: they have always been their own merchants, without the intervention of galleries or other interlocutors, and what they traded the preparatory drawings made on paper by Christo, materializing the ideas conceived by and with Jeanne-Claude. It is not a sale for profit, but rather to support the expenses necessary for the realization, for the materials, for the removals. This shows an aptitude to work in complete autonomy and freedom, which has always led them to refuse even any sponsorship.