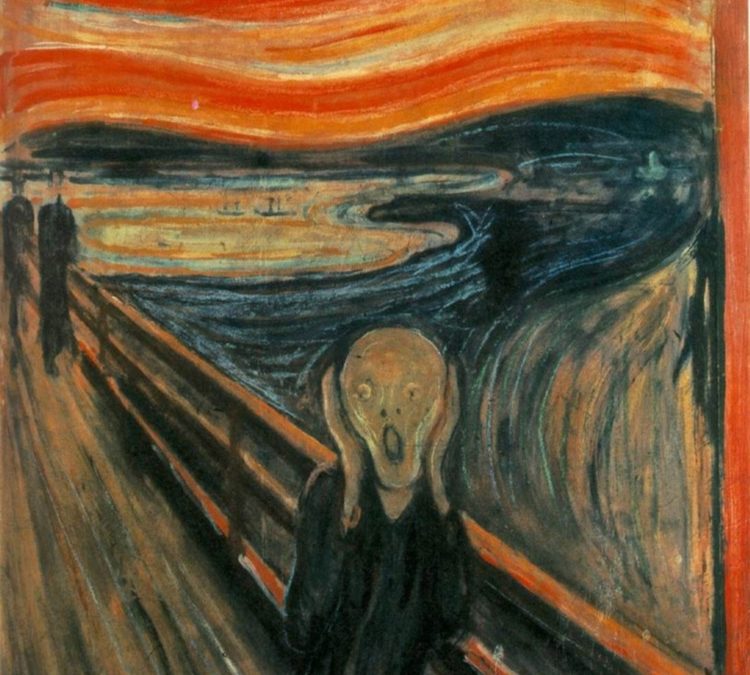

If Munch had recorded his voice what would he shout at us?

These days we hear a lot talking about Sanremo Music Festival, and like every year, Italians are getting ready to watch one of the most iconic programs on national TV.

But speaking of singers and stages, has anyone ever thought about donating their voice?

Courtesy Allwalps

Indeed, among the various donations we can make in terms of social support, it is now possible to donate our voice.

The project is called “Voice for purpose – Let’s give voice to SLA” and comes from the intuition of the Italian actor Pino Insegno.

The idea is to create a voice database that the Ai (Artificial Intelligence) can leverage for patients who have lost theirs due to neurodegenerative disease, and make them regain the expressiveness of eloquence, thus abandoning the cold and blank sounds of current devices.

There are many research centers involved on an international scale, so it is easy for those who wish to participate to access and benefit from the service, which has the double advantage of donating and recording their voice, thus preserving it over time.

People affected by ALS lament the loss of their personal voice as one of the greatest sufferings related to the disease.

All the words we say have an intonation from which others can sense a state of mind or decode a request rather than an exclamation or a doubt.

Human brain and Active receptor, Courtesy medicinaeinformazione.com

Human beings need to express themselves to converse with others, and voice is one of the earliest signs of recognition used in nature.

For example, although they may all sound the same, baby penguins recognize their mother’s voice among hundreds of other calls.

The voice consists of certain peculiarities that make it unique. Tone, cadence, depth, or accent create a particular sound that we somehow link to that or that person. In conclusion, losing our voice is like losing part of our individuality.

Not only does it make us unique, but the sounds emitted by the vocal cords have enormous potential concerning communication. Artists in the past, perhaps without being aware, have been able to exploit this mechanism to give even more power and eloquence to their works.

Just think of Munch’s celebrated Scream: anyone standing in front of his masterpiece does not need to read the title to imagine a defeated cry escaping from the man’s contracted face, and this feeling of anguish and agony is precisely what the painter wanted to convey.

Furthermore, Toulouse Lautrec’s crowded paintings depicting the festive cabarets of the Moulin Rouge would lose their meaning without the boisterous chatter produced by the characters portrayed.

Henri De Toulouse Lautrec, Danza al Moulin Rouge, 1890 – Courtesy allpaintingsstore

In short, when we say: “if paintings could talk!” who knows if the project conceived by Pino Insegno had collected the voices of our ancestors, today we could hear Toulouse Lautrec’s laughter or the dialogues between his dancers?

At this rate, would we be able to make works of art speak?